Ultra Learning: Bracing the discomfort zone

May 2, 2020

I took on a challenge of learning and leveling-up my skills quickly and effectively. In my previous post, I spoke about how I am going to be leveraging the techniques mentioned in the book Ultralearning to practice skills that are way beyond my current comfort level.

For years, I've dreamt of playing certain complex guitar pieces. It stopped there though - I only dreamt of it and did not try enough to make it a reality. So I continued playing what I was comfortable with and ignored the idea of learning new techniques. I would sit for hours continuously and noodle around without any goal or a structured process.

Last year, I broke my wrist and found myself in a fix. I had to relearn aspects of playing the guitar which was extremely frustrating. I stopped playing for a few months until I started reading Ultrealearning. This book kindled the idea to start practicing again, but only this time, in a focused, structured, and deliberate manner.

For the past month, I have been alternating between guitar playing and learning a programming language by incorporating techniques from various books I've read on learning ranging from Ultralearning, Make it Stick, to Thinking Fast & Slow.

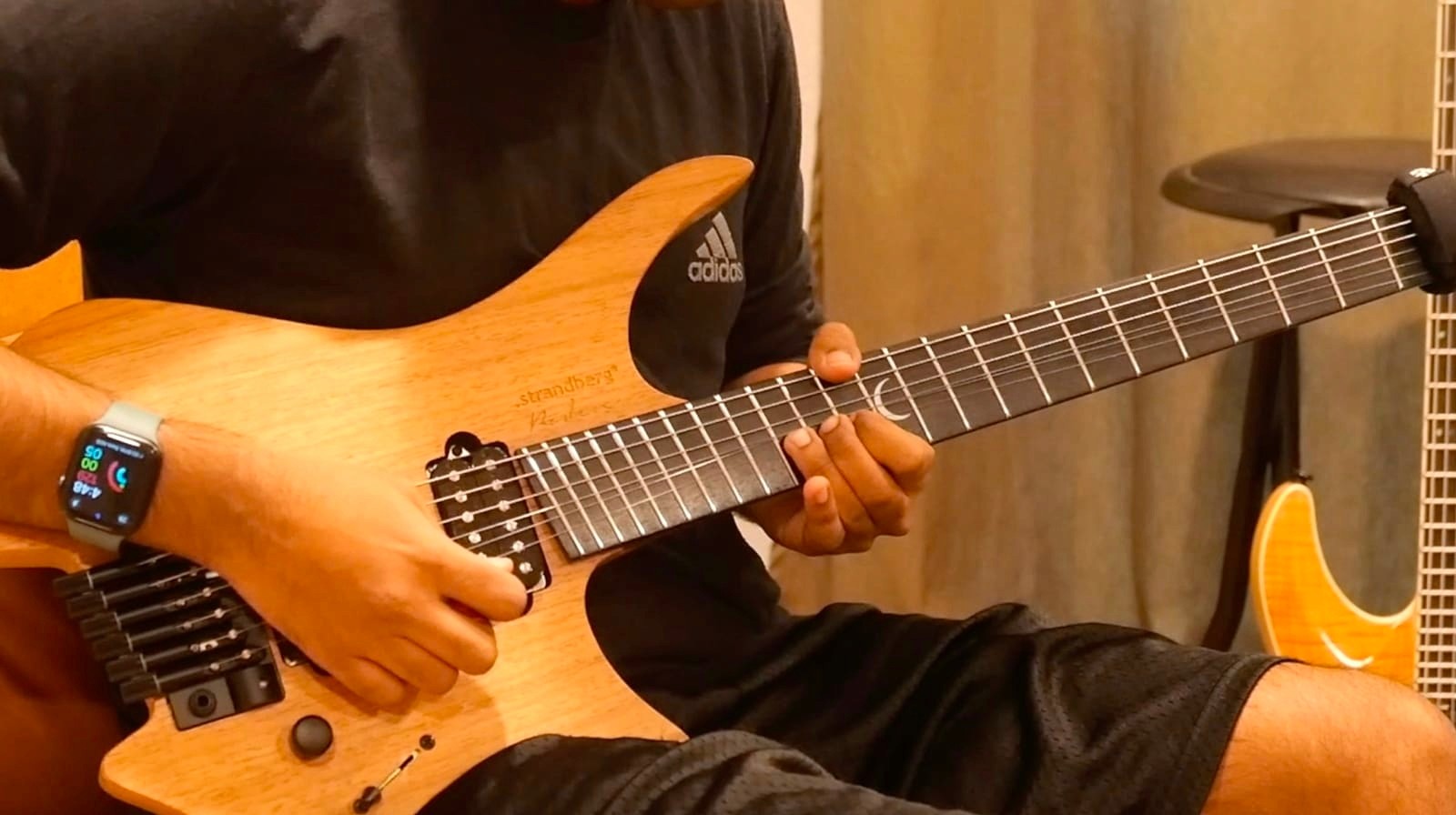

Here's a cover of a song that I considered way outside my comfort zone that I managed to play in a span of 30 days from start to finish.

Below are a few aspects that stood out to me as I uncover more about how I learn -

Diving in head first

Before this experiment, I loved the "idea" of playing really tough sections. I used to watch a lot of videos, watched tutorials, mentally prepared myself to play it, but never really got to playing it. I would flirt with easier sections of the song, but stayed away from the harder sections. I changed that — I started diving head first into the sections that scared me. This put me in a zone of immense discomfort, but this stretched the receptivity muscles. I was becoming more open to being comfortable with the discomfort.

Duration of practice

Prior to the accident, I used to practice several hours continuously. Heck, I remember undergrad days when I'd be playing the guitar 12-13 hours a day. However, now I was constrained with an hour of continuous practice at the most or my wrist starts protesting in pain. I needed to optimize my practice time the most in order to have effective outcomes.

I practiced this song on an average of 30 min a day spread across 30 days - this was about 15 hours of focused practice. Every day, I started with a method called active recall where I consciously tried to play the portions I learnt the previous day before listening to the original song again. This helped me reconstruct what I learnt from the long-term memory.

Which brings us to the process of transferring what you learnt to the long-term memory — Sleep.

Sleep

Over the last few months, I've noticed that aspects I struggled with the previous day, seems a lot easier after a good night's sleep. What I've learnt is that a part of our brain, called the Motor Cortex, is responsible for the execution of movements. The fine finger movements required to hit the right notes at the right time, the techniques that require swift change of finger positioning, the hand-eye coordination, the left-right hand coordination, are all possible because of the Motor Cortex.

When we sleep, what we've practiced transfers from the short-term memory to the long-term memory — so in essence, we complete the "learning" process in our sleep.

Josh Kaufman in his book "The First 20 Hours" talks about optimizing our practice of skills that require muscle-movement 4 hours before sleep. This helps in better consolidation of the skills you learn prior to sleep.

Zoom in and slow down

I've heard a lot of guitar gurus talk about how the key to playing fast is playing real slow — I always never understood this. How would playing real slow, that seems super easy to me, help ? I learnt it does, because if gives your brain the time to process every nuance of the movement slowly. As it registers every small detail, it becomes possible for you to execute at higher speeds faster than you can if you started at maximum speed.

For portions that seemed impossible to play at full speed, I slowed the track down to 50% of the actual speed, turned on the metronome, and practiced at the easy speed for an entire session. Next day, when I come back, I'd up the speed to 60% and so on. Most of the times, when you get the hang of the technique at real slow speeds, it is just a matter of physical capability to move faster.

Feedback is key

I record my entire practice sessions and understand the areas that I am struggling with. This really helps because when playing, the real-time feedback does not point out what went wrong — you just know it sounded odd but what was really wrong? By recording and listening to yourself, you become more aware — you notice the blemishes and consciously correct.

This technique is called Reflection on Action highlighted in the book The Reflective Practitioner by Donald A Schon.

Trust in the process

What I'm slowly understanding is that, the more I adapt, the better I get. For this, I've been extremely honest with myself and spent a good amount of time reflecting on what's working and what's not. This helps me tweak my process and trust it blindly until the next reflection. There have been times where I had the urge to practice a little more which meant losing out on a few hours of sleep, but I brushed the urge and just stopped when the timer went off — this was me blindly trusting that the next day is going to be better because I'd have enough sleep that'll naturally help with my playing.

Next, I've taken up the challenge of playing a song that is years ahead of my current level. I am not entirely sure how this is going to turn out, but I am excited about the process ahead.

For more to come... 🍻🍻

Sign up to my journal to have the digests sent to you directly!